In Chennai recently to attend a conference organised by the Madras School of Economics and the South Asian Network for Development and Environmental Economics, I was honoured to be asked to participate in a panel discussion (Challenges in Mainstreaming Climate Change Adaptation: Research, Training and Policy Possibilities) chaired by Professor MS Swaminathan, the agriculturalist largely credited with the Green Revolution which transformed agricultural yields and food security in India. Although there’s considerable debate about the legacy of the Green Revolution, there’s little about the status of Prof Swaminathan, a truly legendary figure named by Time magazine as one of the 20 most influential Asians of the 20th century. (Find a summary of the conference here)

Many people nowadays talk of the need for a “second Green Revolution” to cope with the threat of climate change to agriculture. Swaminathan remains closely connected to live policy issues at the age of 85, most recently, as is clear from this interview, in the debate within India about genetically modified (GM) crops – a difficult and complex issue which could have an important bearing on the resilience of Indian agriculture to future climate change.

So I listened particularly carefully to his comments during the discussion, in which he talked of food security and water security as the most critical challenges due to climate change. Among the many points he made: that local action will be crucial for successful adaptation to climate change; and that greater “climate literacy” would be needed to enable this to happen.

Illustrating this point, the conference had heard earlier from a farmer from Andhra Pradesh who had been trained as a local “climate risk manager” under an initiative of the professor’s own MS Swaminathan Research Foundation. The job of these individuals is essentially to monitor important climatic data and disseminate it in real time to farmers; farmers accessing this information have seen their yields increase.

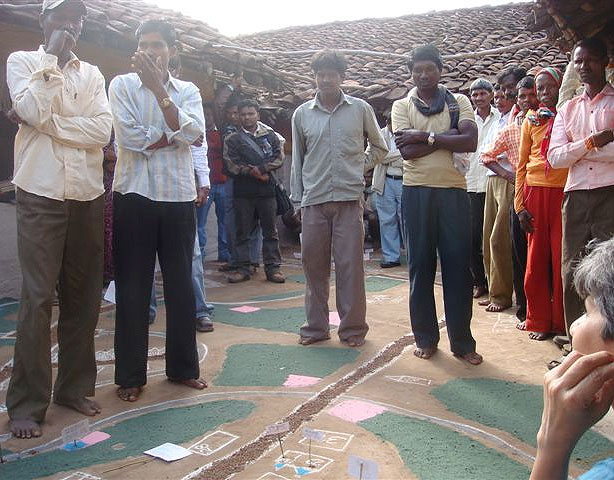

Just last week, Prof Swaminathan’s words came to mind when I found myself in Dindori, a remote rural district in central India, with rates of poverty and malnutrition among the highest in the country. Visiting largely tribal villages and talking to field-level staff, I saw how the DFID-funded Madhya Pradesh Rural Livelihoods Programme, working through institutions of local government, is building the resilience of poor communities through, among other things, helping them improve water availability, boost agricultural productivity, and diversify their sources of income. See this PDF for more information on DFID rural programmes in India.

Many households have also been helped to install biogas plants which use manure – readily available locally – to generate clean cooking gas which is piped into their homes. District Coordinator, Dr Sailesh Shakalya, and other programme staff took me to visit the household whose biogas plant you can see in the photo. Inside, whilst making chai for us on her new, clean and efficient biogas stove, the lady of the house explained how the new device was saving time previously spent gathering firewood, and had also reduced the indoor air pollution which, as noted in my last blog is responsible for so much ill-health across rural India.

The programme struck me as an excellent example of climate change adaptation in practice, illustrating the large overlap between good development practice – especially in areas already suffering from climatic stresses such as drought – and resilience to climate change.

All this has been achieved, however, without explicitly addressing the “climate literacy” that Prof Swaminathan talked about. It left me wondering how much more effective the programme might be if it did so. Work is just getting underway on a similar programme in another state, West Bengal, which I hope will enable us to answer this question. Another illustration, if one was needed, of how climate change forces us to re-examine “traditional” development practice and learn new lessons.

8 comments

Comment by Senfuka Samuel posted on

That is what we need as developing countries to empower us with knowledge and skills than handouts/aid. I have always admired India because of its practical approach to tackling poverty and development issues.

Indeed Prof Swaminathan is an exceptional Agriculturalist and has the passion for empowering poor communities, personally I visited his Foundation and some of the foundation development work in rural communities of Pondichery but it was very satisfying. I also concur with him (Prof) about the need to pay attention to climate literacy many of our people are unaware.

Senfuka Samuel

Uganda

Comment by Malay Dewanji posted on

I have read the report with great interest. Could you please inform me little details of your work in West Bengal, which you have claimed? With all best wishes.

Malay Dewanji

Comment by Shantanu Mitra posted on

Malay:

Thanks for your query. DFID is working closely with the West Bengal Panchayati Raj Dept on its Strengthening Rural Decentralisation programme which focuses mainly on village level planning and governance.

The state govt is soon to issue a Govt Order to ensure that environmental sustainability is taken into account in all panchayat activities. In addition, work is about to get underway on integrating climate resilience more explicitly into the local planning process, and on building capacity on these issues among panchayat members. As I mentioned, I'm hopeful that this will generate some valuable learning on the role of empowered local govts and "climate literacy" in responding to climate change.

regards, Shan

Comment by BIKASH RANJAN JENA posted on

Sir, I would like to know that the total fund provided to the orissa to for poverty eradication programme-to govt and as well to the different NGO. since inception of the DFID prog.

secondly, whether the DFID know that there are starvation death in the Dist of Balangir, that a 4 member of a family members died to hunger & malnutrition within a 3 months. If yes, what measures are taken by the DFID in the said area.

as you know, Balangir is the most poorest dist of India, (outlook India survey)

Thanking you, awaiting your reply

Bikash Ranjan Jena

Dist.Correspondent

SAMAJA-Premier Oriya Daily

Comment by Shantanu Mitra posted on

Bikash,

Regarding your query about DFID funding, may I direct you to DFID's project information database which publicly details much of our expenditure (including programmes in Orissa): http://projects.dfid.gov.uk/home.asp In case you do not find the information you require, feel free to place a query through DFID's Public Enquiry Point http://www.dfid.gov.uk/About-DFID/Contact-us/

We are very much aware that malnutrition is a serious problem in Balangir and other parts of western Orissa, one that is likely to be exacerbated by the effects of climate change. DFID has been supporting the Govt. of Orissa's Western Orissa Rural Livelihoods programme in 4 districts, which includes 350 villages in Balangir. Programme activities include soil and water conservation, access to financial services and food security. Independent impact assessment of the programme reports a decrease in incidence of food deficient days over the last 3 years by over 60% of the poorest households.

In addition we are working with the Department of Health and Family Welfare to develop and implement district nutrition plans across the state, with a particular focus on the KBK districts including Balangir.

If you need any further info on these programmes, please approach the Public Enquiry Point.

with best wishes

Comment by johnny posted on

Well it looks like you are definately ahead of the game with biomethane. The UK has only just recently commisioned its first biomethane plant in Didcot. Its definately the way forward to "greening the gas" and best of all its from natural waste supply that will never run out!

Comment by joydeep posted on

The major benefits of the Green Revolution were experienced mainly in northern and northwestern India between 1965 and the early 1980's and if that could be repeated again then it would surely benefit a lot of farmers and ultimately India would strengthen its position a lot.

BUT the point to be noted here is that excessive use of fertilizers had ill effects in the long run and as a result Punjab still has wells which has nitrate well above the safety level.I think this should be carefully look into,organic farming is one of the best strategies to follow.

Comment by combine posted on

Is burning biogas really "clean" in terms of not creating air pollution? Is there any reason you can't use any type of "manure," IE human waste? Creating energy from both human and farm waste would solve all kinds of problems.