After 18 months my time in Ghana is up. In the frantic rush to pack up, leave and say goodbye I thought I would write down some final thoughts.

Warmth – of the humid tropical sun, of stifling evenings – yes, but of people as well. The richly infectious sound of Ghanaian laughter, humour in the language itself; ‘obruni wawu’ is the name for the piles of second hand clothes donated by well-meaning Westerners for sale in every market – it literally translates as 'dead white man's clothes'. Akpteshie – the fiery sugar cane spirit – the favoured drink at funerals, also known as 'kill me quick' – a name that gives some clues as to its effects. Ghanaian friends and colleagues will strongly disapprove, but I think Francophone West Africa does seem to do the finer things in life rather better – food, music, fashion, beer... But you just need to look across the rest of the region to see how well Ghana does in some of the things that really are more important to people's every day lives: ethnic and religious tolerance, a free press, (in many ways) a booming economy, a vibrant democracy. Ghana doesn't have the wide open landscapes of Namibia, not the stunning landscape and wildlife of East Africa, not even the beaches and mountains of Sierra Leone or the skyscrapers and public transport of Abidjan. What it does have is a sense of pride in a cohesive national identity, in its democratic tradition. Not the scars of apartheid which still run below the surface of South Africa, nor perhaps the growing geographical and religious divides of other West African countries.

Wrought, perhaps, in the heady days of the 1950s and 60s after Ghana became the first African nation to gain its independence in 1957, this democratic sense was then submerged in murky periods of military rule, coup and counter coup through the 70s and 80s, before resurging in the 90s.

The current President, John Mahama wrote his memoirs My First Coup D'Etat about his time in these so-called "lost decades" in Africa: years of authoritarian rule, stagnation in politics, the economy, the arts. But in it, he writes about how for some people like him, these lost years actually became an awakening, a time they began to find their own voices. The book opens with the poignant memory of himself as a 7 year old boy returning home from school to find his home empty, his father had disappeared; a minister in Nkrumah's government, he had been imprisoned following a coup. Mahama writes that this moment was an "awakening of consciousness", a coming to the realisation that this was not how things should be, and a determination to try to change them.

Kenyan author Ngugi Wa'Thiongo wrote a brilliant Garcia Marquez-esque novel called Wizard of the Crow, which brilliantly satirises the venal African kleptocrat in a fantastical but politically astute way. It shows a wickedly imagined stereotypical image of an African leader in those "lost decades", and one that still might strike a little close to home for some leaders today, but not in Ghana. It is a vision that does not seem to fit in Ghana's political and democratic history, or alongside Mahama's warm, personally felt memoir.

The democratic tradition, the cohesive sense of national identity which had been forged in Ghana's early years re-emerged as democracy returned in the 1990s; it's a democracy that can be loud, discordant and messy, and works through complex overlapping webs of ethnic and political allegiance; but people really do feel like they have a voice. This sense of democratic pride came out most clearly to me in December's Presidential elections. Taxi drivers vigorously debated the different parties' education policies, security guards would listen to the radio rapt to the epic 4 hour long (!) Presidential debates (partly funded by UK aid). As an election observer (read my blog about it here), everywhere I went I saw lines, hundreds long, of people waiting patiently in the baking sun for the chance to cast their vote, old men who had queued out in the open since the night before to have the chance to vote when polls opened at 7am. It was a privilege to witness a small part of Ghana's democratic history.

And even in 18 months, I think about the growth of Accra I've witnessed – every day a new building going up, every night a new bar or restaurant opening, and all the time the traffic gets worse, battered tro tros jammed full of people lumbering along the roads billowing out acrid smoke. I think about the dynamism of some of the young people I met – some born and bred in Ghana, some returning from studying abroad, or children of Ghanaians who are visiting the land of their parents for the very first time. Where 20 years ago the talented people were leaving the country, now many are coming back. And they are young, energetic, creative, entrepreneurial - I think of my friends who've built property businesses from scratch, started think tanks, built mobile applications.

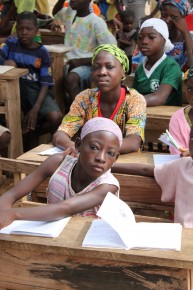

And then I also think about the people this growth isn't really touching at all - villages way out in Upper West region, hours from the nearest tarred road, clinic or electricity connection. Schools where teachers haven’t turned up, where children don’t have books.

I think about my visits to UKaid-supported 'School for Life' classes. Seeing kids who had been forced to drop out of primary school, or who never had the chance to join in the first place, getting a second chance at education - something that should be every child's right. Then meeting the parents, hearing them explain their determination that their children should have a better opportunity than they did. I think of the challenges ahead. A booming economy, but one still largely reliant on commodities and riding high on the first wave of reforms that came with democratisation in the 90s. Now as a middle income country Ghana really has to push for the second wave – reforming its public institutions and the way it manages its money, diversifying the economy – otherwise its progress will stagnate. I think about the contrasts. The juxtaposition of what seems to be tradition and modernity – chiefs in traditional dress welcoming you to their village, with one hand pouring the customary bottle of schnapps you've brought them onto the floor as an offering, and fiddling with their smartphones with the other.

Meeting the Asantehene – who went from working in Brent borough council to becoming King of the Ashanti – who leads one of Ghana's biggest ethnic groups and a royal lineage going back 300 years, who inherited a palace and a bling gold jewellery collection that would put most self-respecting rappers to shame. (See here)

The variety of geography – rain-forested coastal Western Region, to verdant green and hilly Volta Region. The regions up north - the dry arid savannah where the harmattan wind sweeps in every January bringing the fine dust from the Sahara which filters out the sun. Here it's a different world from the sprawling metropolis of Accra – mudcracked houses and dirt roads, subsistence farmers growing maize, cassava and rice.

Visits to companies like Blue Skies - a firm previously supported by UK aid that works 24 hours a day taking fresh mangoes and pineapples from smallholder farmers and turning them into the packets of freshly chopped fruit you see on the shelves of Sainsbury's and Waitrose a few hours later. And then less sustainable business models - towns I've been to in Ghana's central region that are like the wild west, where small scale gold miners raze the ground and turn the rivers milky white with toxic chemicals as they dredge them in search of precious flecks of gold.

My favourite place in Accra is the area around Jamestown –the oldest part of the city - ramshackle fishing villages, and crumbling colonial buildings. Famous for producing World Champion boxers (see here), I used to go there to learn boxing myself, picking my way across the courtyard littered with shattered tiles, broken bricks, and clapped out cars to find the Attoh Quarshie gym, a small dark room, with a couple of punch bags and a ring, and walls covered in tattered old posters advertising boxing matches. No fan or AC, only narrow windows, just wide enough to let the smells of smoked fish and burning rubbish in off the beach. I helped coach Ghana's national rugby tournament as they played in a West Africa Sevens tournament. The World Cup this was not – the only support they received from the government was the loan of a minibus to take them to Togo (which broke down). The 'athletes' village' was mattresses on the floors of the changing room, and they only had 1 supporter (who doubled as the bus driver). But the guys stood proudly singing the Ghanaian national anthem with tears in their eyes.

I think about people we have lost – my friend who died in a traffic accident, relatives of colleagues and friends. Traffic lights that don't work, street lamps that won't light, roundabouts that cars don't go round. Frustration, elation and enervation; plans that don't work and work that doesn't seem to plan. Endless battles with unreliable water, mobile reception, internet and electricity.

Rainy season – torrents of water pouring down, rapidly blocking storm drains, flooding streets. Green tomatoes, green lemons, mounds of dried fish, joints of meat with clouds of flies gathering overhead, chickens – dead, alive and everywhere in between. And when you drive out of town – towers of pineapples tasting sweeter than you could ever imagine, cracked open coconuts cool and refreshing inside. Fishing boats along the coast - giant hollowed out tree trunks painted in bright colours with bible quotations emblazoned on the sides. Fishermen with gnarled hands mending nets. Heat and sweat, lights out and traffic jams. Sitting in the back of a pick-up truck in the tropical sunshine, coated in layers of dirt, bones aching from potholed roads.

Driving through towns and villages on Sunday mornings, people flocking to church in their Sunday best –loud African print skirts, brightly polished shoes. Churches that are Anglican, Methodist, Roman Catholic – and every other denomination imaginable.

Roadside hawkers swooping in as traffic lights in town turn red – selling you fried plaintain, sachets of water and phone credit, but also items less immediately plausible as impulse buys. I've seen vendors selling stepladders, games of cluedo, broken mirrors, power drills and tummy trimmers.

I'm moving to London to work for DFID there. But I’m sure I’ll be back.

6 comments

Comment by Lee Walters posted on

Thanks to Henry Donati and the DFID for all those development projects that put smiles on the faces of all those children.I believe we could quicken the pace of development in Africa if we adopted tools such as DevHope. It is a social media that brings to the fore an innovation to help organizations realize much easily their projects. Among others, it uses crowdfunding to obtain funds for development. It also helps organizations transfer services,not money for projects. This eliminates the possibility of embezzlement, corruption etc.This is the first of its kind. There is more for you on DevHope

Comment by Jayden Robinson posted on

Henry, I absolutely agree with this your observation, "Ghanaian friends and colleagues will strongly disapprove, but I think Francophone West Africa does seem to do the finer things in life rather better – food, music, fashion, beer... But you just need to look across the rest of the region to see how well Ghana does in some of the things that really are more important to people's every day lives: ethnic and religious tolerance, a free press, an (in many ways) booming economy, a vibrant democracy."

I'm from the biggest African Nation Nigeria, but I moved my family to Accra last month March, and one thing my family is finding difficult to cope with is food....etc. I have travelled to some francophone countries and as you said...you just need to look across the rest of regions.....!

Well I'm a researcher and I have got the privelege to work on DFID assisted projects in Nigeria and other West African Countries. So, I will be glad to consult for DFID here in Accra. Do not hesitate to contact me if you have research projects here or elsewhere in our region.

Comment by Nicole Goldstein posted on

A brilliant post - capturing the mood of Ghana. Your post certainly rivals Lionel Barber's (FT editor) 12 days across West Africa piece. You sum up all that Ghana has to offer and the possibilities that lie before this hopeful nation. What an insprining homage! We will miss you in DFID Ghana but we are looking forward to hearing about your work in the humanitarian division.

Comment by Henry Donati posted on

Thank you all for your comments - it's always nice (and surprising!) to find people do actually read what you write..

Comment by Genevieve Wastie posted on

I loved reading this Henry - thank you!

Comment by Anita Ogilvie posted on

Thanks for such a fantastic trip down memory lane. A brilliantly evocative piece - it took me right back to the Ghana I fell in love with when volunteering in Kumasi in 2000.