“I’m not sure I’m going to uni,” Jordan Casey said recently. “But I’ve got five years to decide.” The Irish 13 year old was speaking at the Guardian Activate conference I attended – billed as exploring how digital innovation, technology and openness are transforming the world.

He began programming at the age of nine and now runs his own mobile games start-up called Casey Games in Waterford, Ireland. Between living a normal teenage life of hanging out with friends and playing football, he also spends a few hours a day on his company which now has three staff and has already produced several successful iPhone and Android apps. He is also a hot ticket on the speaking circuit, though he has to make up the class time lost in special after-school sessions.

Composed and eloquent, Jordan was speaking on a panel of young tech entrepreneurs about whether university is a worthwhile pursuit. There were mixed opinions about the value of structured learning when you’ve used your free time to carve out a career long before filling out a UCAS application. As the young entrepreneurs spoke, the collective sense of depression among the much older audience was palpable. “I’m more than twice his age!” tweeted one delegate.

But this got me thinking about the importance of time and age in one’s digital life. Young people in industrialised nations are growing up completely native to the connected world. Industry insights firm Nielsen calls this group Generation C. Because they have time to explore and no preconceived ideas about what’s possible, they learn to use tools to their advantage, to do things that matter to them. In Jordan’s case, his parents didn’t realise until later on that he was making games, not playing them.

Much has been said about the importance of getting coding for kids into the national curriculum, and Jordan also spends time encouraging other kids to code. Young Rewired State has been putting on hack days for young people since 2009. Their primary focus is to “continue to find and foster every young person driven to teach themselves how to code, how to program the world around them.” Their history alone is a fantastic insight into how quickly this agenda is moving.

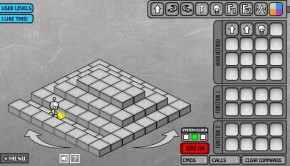

What seemed like a distant debate a few years ago has become highly relevant on a personal level too – my six-year-old son has recently started playing with LightBot– a puzzle-solving game which teaches basic coding principles. The other evening I caught him playing it on the tablet he’d smuggled into the bedroom when he should have been asleep.

Indeed, time and inclination are essential for navigating the new digital landscapes. And time is precisely what many people lack as adult responsibilities pile up. Even a few of the most seasoned digital professionals I know admit they no longer want to keep up. “I only use Instagram to keep an eye on my daughter,” one father in his forties tells me. With broadband access set to almost treble between now and 2017, the speed of change is even faster for young people (and their parents!) in the global South.

Young people entering the workforce now are not only accomplished videographers, photographers, graphic designers, coders and TV presenters, but often thought leaders and business people too. Hence the importance of putting young people at the front and centre of any digital work, especially communications. They have a lot to teach us.

At DFID we need to be thinking about how to adapt to this new playing field and how best to engage with young people, not only as an audience for our communications but as important actors in the wider development sphere.

Recent Comments