Love it or loathe it, 1 of the grand challenges for education in developing countries is how to integrate technology in a cost effective way that has impact.

In a paper released this month, McKinsey report that over 67 million smart phones are in use across Africa today and 50% of Africa’s urban residents are online. They also estimate that by 2025 Africa will be home to 600 million internet users - many of whom will be children - contributing $300 billion to the continent’s GDP.

Epic stats aside - the fact is, educational technology is rapidly becoming integral to the way children live and learn. Whether it’s students holding teachers to account through SMS in Mozambique, children in Ghana using e-readers to access stories in their mother tongue or teachers using open source, offline applications such as Tangerine to simplify and improve the quality of data collection analysis edtech is here to stay.

As I implied in my last post, there are now so many edtech offerings, our challenge is not whether we consider technology, it's identifying which technologies are most suitable to confront specific challenges.

Stop Press! Some edtech works

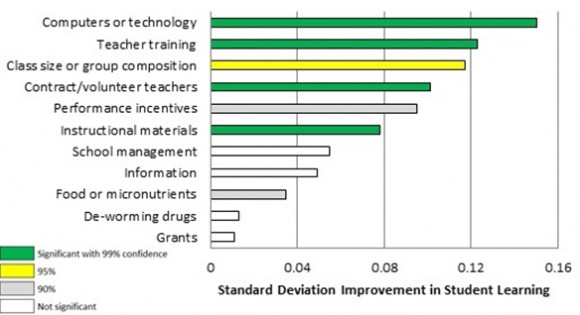

Patrick McEwan’s recent meta-analysis of 76 randomised control trials conducted in primary schools across the developing world found that interventions using computers or instructional technology had the largest impact on learning outcomes of the 110 treatments analysed. This is startling and important. Below is McEwan’s now regularly cited evidence.

More specifically, both McEwan and Kremer find that when computer programs are tailored to the needs of students i.e. when student needs come before technology - computers have a positive effect on learning outcomes. Kremer’s study focuses on an individually paced computer assisted learning program in India, which increased test scores by 1.54 standard deviations for every $100 spent. A salient finding which must be absorbed.

As David Evans of the World Bank and others have noted, this is striking evidence. It should prompt us to rethink some of the assumptions we make when discussing the role and potential of technology.

Stop Press…again! Some edtech doesn’t work

Understanding the circumstances in which technology has been proven to work is as important as knowing in what circumstances technology has failed.

Striking as the results above may be, on their own they do not tell even half the story, which is fragmented and complex. McEwan finds that technology is often not impactful when it replaces teacher’s time, when it is implemented with no training and when a plan to meet a specific educational goal is not adhered to. This corroborates good practice previously identified by Mike Trucano and others: that any technology alone has little to no impact.

Given the costs involved in some edtech investments, incorporating edtech into programs carries big risks, and, in lieu of a rigorous evaluation data that synthesiszes and compares the evidence, far from guaranteed benefits.

We need to be knowledgeable about disastrous uses of educational technology to spur better practice and guide policy.

Access to technology has the potential to empower, not prescribe

Arguably, 1 of the most exciting things about edtech is the potential it has to give people the tools they need to design their own educational resources. As such, some aspects of edtech represent an exciting opportunity to support a participatory approach to development.

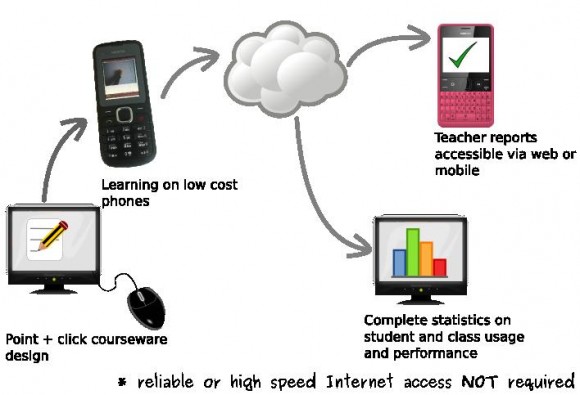

One such example is Ustad Mobile, a platform which allows anyone to build their own digital learning activities using a simple ‘point and click’ computer program. So anyone, with even basic computer skills, can design and make available e-learning courses which are contextually relevant and tailored to the needs of their audience. When developed, resources can be downloaded to any device: laptops, tablets or most likely, mobile phones.

DFID is working with Ustad Mobile through Child Fund in Afghanistan, a Girls Education Challenge funded project. There, Ustad is providing literacy courseware that matches the Ministry of Education literacy curriculum, pre-installed on mobile phones.

Practice and policy?

In light of the above, it seems clear that DFID should have an adaptable edtech policy which is continually informed by what DFID and others are doing, and also, articulates a road map. However, in a field defined by constant iteration, in which ideas become reality in a short space of time, one may be tempted to ask – is it even possible to write a policy?

While an edtech policy may not prescribe any ‘solutions’ (and nor should it) a policy that commits to staying informed and engaged with the evidence is necessary. Furthermore, given the lack of high quality evidence in this field, a commitment to robust evaluation is also crucial. Finally, DFID’s edtech policy must continue to embrace and attempt to answer the questions: why should we use this technology and how should we use it?

2 comments

Comment by Mike Dawson posted on

If one takes "effectiveness" to mean roughly "results delivered per amount spent" then there is a lack of evidence across the field of interventions because of lack of comparable cost data as per McEwan and Kremer. We have ghost schools (which exist only on paper for purposes of officials collecting salary payments anyway) that we only know if physical buildings are actually there thanks to drones and satellites. How are we going to find if anyone is going there, let alone learning anything? Quite likely technology needed.

I'd also argue that there are few offerings that meet what is needed on the ground in developing countries. No Internet access 24x7, no smart phone, no solution for creating learning content available to you except Ustad Mobile/eXeLearning. Online cloud attendance trackers and things needing servers always available would be useless. No solution for students taking their own exam offline and some tools mentioned have no working documentation or available downloads.

Comment by tin nhan noel 2013 posted on

Developing countries to apply the technology in education is extremely difficult. Because there are two reasons: First, financial problems, 2nd skill is how to use technology effectively 🙂