I’m not sure whether it was tempting fate on Friday the 13th, or an early Valentine’s gift to the nation, but Tanzanian President H.E Kikwete boldly launched a new national Education and Training Policy (ETP), the first for almost 20 years.

In the blazing sun at the Majani ya Chai (‘tea leaves’: built on old tea factory land) secondary school near Dar es Salaam Airport a large crowd had gathered. Boy scouts handed out water, the national flag fluttered and the army band sweated and practiced the national anthem Mungu ibariki Afrika (God bless Africa).

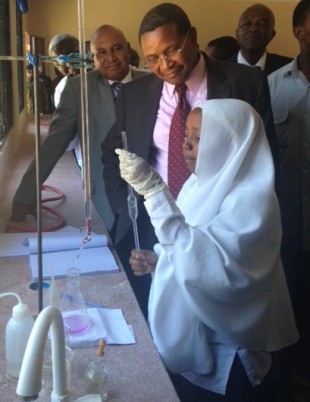

I waited with a large group of officials and dignitaries and as the cavalcade arrived, we joined the President on a tour of the school’s new science laboratories. A presidential decree to build labs at all secondary schools was issued last year. Inside we witnessed a number of surprisingly confident students ably demonstrate practical experiments: the volume of irregular shapes, detecting starch in potatoes, how to perform chemical titration. Everyone was impressed by the students’ ability (and potential), and the simple but impressive infrastructure.

This was one way to get rapid results, but how quickly or how well much poorer, remoter rural areas would be able to construct labs is debatable. Tanzania over the past decade has greatly expanded access to secondary school with a wave of new rural ‘ward’ schools, but many have struggled to offer an education of minimal quality as the 'crisis debate' ran around low pass rates in 2012 and the subsequent Big Results Now (BRN) initiative.

Then came the ETP policy launch, with a long Presidential speech delivered under the midday sun and with a range of celebratory music and drama to entertain the crowd.

Some major initiatives and changes were announced. Of note was a proposed expansion of free and compulsory’ education to 11 years of nursery, primary and secondary schooling. There was also a proposed ‘one text book’ policy for each subject in each grade, regulations on private school fees structures to make them more accountable and a move to using Swahili as the medium of instruction in secondary school (as it is in primary).

These have potentially huge costs and challenges to introduction; some cynics noted it had taken close to a decade to research and release the new policy, how long then to implement it? More and better universal education, starting from a younger age is undoubtedly welcome, but given Tanzania’s demographic projections this would require an enormous expansion. Child mortality is thankfully dropping, but demographers predict a continued expanding ‘bulge’ of young people for 20 years, even if fertility rates start to drop soon.

Private school regulation, textbook monopolies and the use of English are likely to prove controversial, how to implement the new policy will give us plenty to discuss with the Tanzanian education officials and a new phase of education sector planning is due to support soon with assistance from the Global Partnership for Education and UNESCO’s education planning institute, IIEP.

Just as President Kikwete was making his officials sweat on the school lab programme, my donor colleagues and I felt the ‘heat’ as he glanced our way and switching to English, politely requested our support to implement the policy in the years ahead. DFID is a long standing provider of assistance to Tanzania's education system and we look forward to supporting the new policy in a coherent, constructive and effective manner.

Keep in touch. Sign up for email updates from this blog, or follow Ian on Twitter.

2 comments

Comment by Jean Van Wetter posted on

Nice article! What do you think about the use of Swahili as a medium of instruction in secondary education?

Comment by Jim Tomas posted on

Great work, guys! The education is something really important. We need to develop it everywhere.