Last week was my first visit to the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW), an annual event that has been held at the UN since 1946. Over 100 ministers and 8000 civil society advocates attended, with events ranging from set piece plenary sessions where ministers deliver their national statements, to side events on every issue you could imagine.

This year, we were celebrating 20 years since the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing agreed powerful commitments for advancing women’s rights, known as the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action.

That ground-breaking declaration was and still is a blueprint for what needs to happen to advance women's rights – but has yet to be fully realised anywhere in the world.

That ground-breaking declaration was and still is a blueprint for what needs to happen to advance women's rights – but has yet to be fully realised anywhere in the world.

I had long heard reports of CSW. Often I heard that progress seemed difficult to achieve. Indeed, it was challenging enough to stop the world moving backwards on women's rights, especially in the sexual and reproductive rights which must underpin women's autonomy.

Having heard about CSW for so many years without ever being a participant, it was extraordinary to represent the UK in that famous UN General Assembly Hall.

But one of the aspects of the multitude of side events that really gave me a sense of progress and movement was on combatting violence against women and girls.

Twenty years ago, before Beijing, I doubt that there would have been such widespread and determined focus on something that has for so long been in the shadows, barely talked about.

But now, something that was assumed to be always with us – to be tolerated, endured – is at last being challenged.

Rape is recognised as a weapon of war. Attempts are made to work out how we prevent sexual violence in conflict. Sustained work is going into eliminating female genital mutilation (FGM).

We have a very long way to go to get protective laws into place, and even when we do, to ensure that they are in fact implemented. Nothing will shift unless we shift the social norms that underpin how women and girls are viewed. Social norms need to be revolutionised. And the first thing is for violence against women and girls to come out of those shadows.

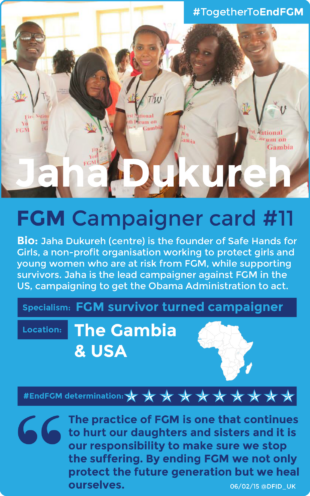

I found the stories of FGM survivors moving beyond all measure. At a Guardian event chaired by journalist Maggie O'Kane, Jaha Dukureh told how she had undergone radical FGM as a baby. She was engaged to an older man when she was 7, and after the death of her mother, she was sent, aged 14, to America where her 40 year old bridegroom awaited her. She was cut back open in the most painful experience of her life, ready for this marriage. Her terrible experiences of her new married life, and the appalling pain she suffered, instilled such fear in her that the marriage collapsed within months.

She counted herself fortunate: she stayed in the States, later took herself through college, married again and had 3 children. It was when she had her daughter, and knowing that her little girl must never be cut, that she started to work to end FGM for other little girls.

This took her first to work within her community in the US, and then back to her community of origin in the Gambia. While there, her new stepmother gave birth to a little girl. Jaha knew that the new baby would be cut within days of her birth. She thought that if she could not stop her Imam father having her new sister cut, then what worth was her own work?

Her success in persuading her father to leave his newest daughter intact, and breaking the generational cycle, Jaha sees as one of her greatest achievements. The beautiful, articulate, impressive Jaha is now a Girl Generation adviser. The Girl Generation, funded by DFID, is supporting the Africa-led movement to end FGM.

The UK is playing its part to seek an end to FGM worldwide within a generation. DFID is funding a 5-year, £35 million programme to reduce the prevalence of FGM in 10 countries by up to 30% and contribute to ending the practice within a generation. We are working in 17 of the worst-affected countries to challenge social norms which underpin this practice.

So, as well as bringing these issues out of the shadows, we also need to know what works to shift social norms. The OECD has developed a way to analyse the patterns of social norms and compare them across countries, called the Social Institutions and Gender Index. This shows that you can measure these things that many believe are too difficult to measure – and can challenge and change them.

Addressing social norms needs to underpin how we approach the new Sustainable Development Goals that will replace the Millennium Development Goals this year. That’s why the UK is linking up with other countries to talk about how they will prioritise gender equality in negotiating these goals.

Hearing and seeing the outstanding young activists at CSW gave me confidence that we are indeed within sight of the goal of ending FGM, violence against women and girls, and so many other pernicious social norms.

As I saw an arm slide around the shoulders of a delegate in front of me as we heard of terrible cases of FGM being carried out, I knew that the person thus comforted had herself experienced such terrible trauma. It brought home to me that not only must FGM end, but also that it will do so, and that the brave survivors are doing extraordinary work to achieve this.

Sign up for email updates from this blog, or follow Lindsay on Twitter.

Recent Comments