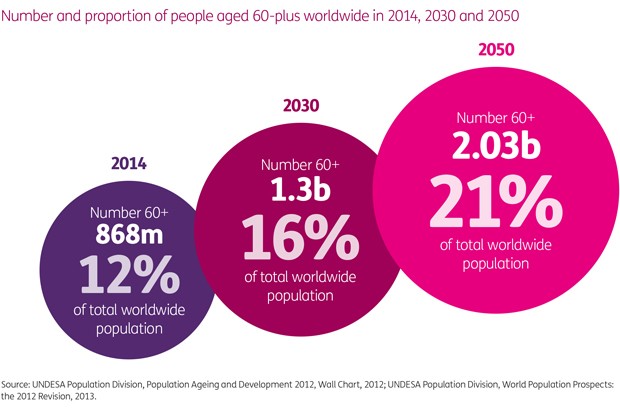

An astonishing transformation is taking place that has until now been absent from mainstream development thinking: global ageing. Its absence is even more surprising as the evidence makes clear that demographic changes are affecting developing countries the most. Currently about one in ten of the population is aged 60 or over; but within a generation – 2050 - this ratio will soar to one in five. Two-thirds of the 868 million older people alive today are in developing countries; and of the 2 billion people expected to be over the age of 60 by 2050, over three-quarters will live in low and middle-income countries. The rate of change is phenomenal.

What we do with this information will determine whether this new reality is something to welcome or be feared. This is why the World Health Organisation’s new “World Report on Ageing and Health” released today on the International Day of Older Persons is so important. Its message is clear: celebrate our longer lives; invest in older people; but most importantly – be prepared.

We are used to thinking of ageing as a ‘wealthy country’ phenomenon. But this is an agenda that is as meaningful for the young girl growing up in Vietnam today as it is for the 65 year-old mother-wife-daughter living in Kenya who looks after three generations of her family.

Ageing is a development fact. Better education, stronger economies, improved water and sanitation, better health care, more secure societies all lead to an inevitable conclusion: increased longevity. And a greater number of older people.

Success therefore looks like an older person; if – and this is a big ‘if’ – later life is lived in good health, with adequate income and as part of a supportive community environment.

The findings from the WHO report unfortunately tell us that this is not the case more often than not. We are not living longer in better health and older people continue to face multiple levels of discrimination. Whilst retirement and a pension are considered to be a right in the UK and other wealthy countries, only one-quarter of older people in low and middle-income countries have some form of pension. Older women in particular experience horrific levels of violence and other forms of abuse simply for being older and female.

So what does this mean for development cooperation? To help us understand, let us first look at the story of Anne, who lives in Kenya’s Central Province.

Anne is a 65 year old widow who has 7 children and many grandchildren. She is responsible for 8 of her grandchildren who live with her because she lost her son and daughter to AIDS-related illnesses. Anne also looks after her 103 year old mother-in-law Elisabeth.

In addition to looking after her household, which includes farming a quarter-acre plot a 2 km walk away, Anne works as a peer educator on HIV issues and as a home-based carer for older people through a programme initiated by our partner HelpAge International.

Clearly, Anne is an exceptional individual, but aspects of her story are repeated many times over in all parts of the world. What Anne helps us to see is the vital role older people are playing in their families and the wider community and that later life does not have to be a time of dependency.

Healthy ageing is more than the absence of disease. Most older people, however, will eventually experience multiple health problems and chronic illnesses. Managing and preventing these non-communicable diseases is a health priority that is thankfully being pushed higher up the global public health agenda. For example, David Cameron made tackling dementia one of the cornerstones of his G8 agenda. But current international efforts fall far short of what is necessary and older people still risk being marginalised in health policy, practice and monitoring.

Focusing on ageing and health is actually an agenda that spans all ages. The WHO report helps us understand how governments can help a girl or boy growing older in a lower or middle-income country realise their potential at any age. A child born in Myanmar in 2015 can expect to live 20 years longer than one born just 50 years ago. We need to ensure this girl or boy lives these extra years in good health.

To achieve this, the WHO - together with its member states and other stakeholders - is developing a Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health. The newly agreed Sustainable Development Goals leave no doubt that Governments, UN agencies and civil society stakeholders alike must take into account the health of a person at all stages of their life. The WHO report and action plan are important tools for bringing this about.

Author of this blog - Ken Bluestone - leads Age International’s policy and influencing work.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Please note, this is a guest blog. Views expressed here do not necessarily represent the views of DFID or have the support of the British government.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Recent Comments