Nelson Mandela's legacy in Tanzania is rapidly expanding, as I learnt just days after returning from Washington DC last December, where the White House flag was at half mast as a mark of respect.

Nearly a decade after Mandela met the then World Bank President James Wolfenson, a network of Pan-African regional science and technology research universities are being established. Their mission is to empower and build African capacity in home grown scientific and research. The founder's wisdom is inscribed beneath his statue at the Arusha based Nelson Mandela African Institute of Advanced Technology (NM-AIST), which really says it all:

Education is the great engine of personal development. It is through education that the daughter of a peasant can become a doctor, that the son of a mineworker can become the head of the mine, that a child of farmworkers can become the president of a great nation (extract Long Walk to Freedom).

The statue had garlands of fresh flowers when I first visited the week after Mandela's death. DFID colleagues and I had gathered nearby for a professional development conference, but were taken to visit 1 of the NM-AIST's public health research programmes on defluoridation by Hans Komakech.

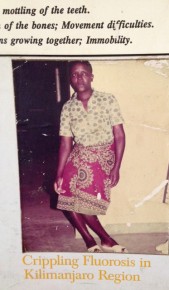

Defluoridation programmes like these hold interesting results. As most people know, a lack of fluoride in our water can allow dental decay to occur and cavities to form. However a concentration above 1.5mg/l in the water supply can lead to discolouration of the teeth and in higher concentrations serious skeletal problems and chronic weakness and pain. Many parts of the Rift Valley have naturally high concentrations of fluoride in the water - a local village is known as Maji ya Chai: Swahili for 'tea water' due to the mineral rich red-brown water.

The Ngurdoto Defluoridation Research Station has been established to seek practical solutions to these problems. Mr Mkongo, the research head, has battled long and hard for 20 years to devise a low cost, but effective filtration system to defluoridate water using fragments of bone-char: cattle bone part burnt in a way similar to charcoal manufacture. A household unit can be produced for around $20 that purifies enough water for drinking and cooking with a $5 bonechar filter pack that would last for around 6 months. After being tested in the community, all that was needed was finance and a business model to scale-up, mass produce and roll-out.

Whilst we visited the research station, another group of my colleagues visited the PPP at the Arusha A to Z Textile Mills that produces long-lasting anti-malarial bed nets, an African based solution for another better known public health problem.

The NM-AIST Ecolab's role is to conduct detailed public health monitoring and evidence gathering on how best to scale up local innovations that could potentially help thousands of communities up and down the Rift Valley from Ethiopia to Malawi. The ambitious vision of Vice Chancellor Professor Burton Mwamila is to greatly expand the volume and disciplines of research at the institute and incubate innovation and links with both industry and the communities to promote sustainable, economic development and growth. This is likely to be challenging given the institutional and financial constraints faced by Tanzania, but I wish NM-AIST every success and look forward in the future to Tanzanians greeting me with even more dazzling smiles!

We did come away curious why one could only buy imported toothpaste with added fluoride in the local supermarkets...

Keep in touch. Sign up for email updates from this blog, or follow Ian on Twitter.

Recent Comments