Designing a large performance or results based education financing programme in Tanzania has certainly been a challenge over the past months. In particular getting the indicators right: how they can realistically be linked to achievable targets that both stretch and incentivise stakeholders, whilst holding up to more robust scrutiny that they have meaning?

My current bedtime reading is Ben Ramalingam’s fascinating book: Aid on the Edge of Chaos. Not a light read, the author probes the very premise of how aid agencies strategise and plan, detailing the many short-comings of linear models and assumptions that ignore the inherent complexity and dynamism of the situations we seek to influence. Complexity is a recurrent theme in Duncan Green’s provocative Oxfam blog From Power to Poverty. The longer I work in developing countries the more I believe the context, or political economy matters, and is essential to try and get to grips with, if we are to be influential and smart.

Tanzania's controversial rollercoaster examination rates have in 2013 'bounced back' from 2012 lows, amidst speculation on cause and effect. I joined a discussion with senior government officials in Shinyanga region last week, who were keen to attribute positive influence to Big Results Now! initiatives, both local and national. The case remains unproven, but in earlier meetings with government and development partner colleagues, it was decided that they were too volatile to link to the new education-financing instrument.

Many 'complexity' examples arose later as we drive out to the green rural plains of Shinyanga. Whilst recent rains had been good, this area often experiences drought and food insecurity. At one of the new water schemes DFID support it was easy to see the difference reliable water makes: the price of bucket has gone down 5 fold and it’s clean enough to drink straight from the tap. Community management and cost recovery looked impressive, but was the local government likely to install a new generator or drill a new borehole in the case of catastrophic failure in the future?

At Nhumbili primary school a rain water harvesting scheme had been set-up a few years ago with Oxfam support, but it appeared only partially used and only tapped a quarter of the roof area of the classrooms. Community members and teachers told us water of low quality was collected from a well about a mile away - was there a disincentive to keep the roof collection system working? Or if you could order your female students to fetch water for you, would you not bother to?

However the most perplexing theory on the thorny issues of examination results came up when I enquired about the lower pass rates of girls in the end of primary examinations. It wasn't time out of class on chores, instead it was suggested that some parents deliberately encouraged their girls to fail on purpose, so they could be withdrawn and married off, triggering dowry payments in livestock. Local officials explained that regulations required all students passing the exam to be entered into the rapidly expanding network of rural secondary schools, and this could trigger this perverse set of consequences.

Whilst we have retreated from linking finance directly to examination scores, the use of a measure of reading fluency is gaining traction, partly due to the emergence of the Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA) methodology that tests students’ emerging literacy skills for accuracy and speed. At a certain speed and accuracy threshold (it varies between languages, but is often around 50 word per minute), student gains sufficient fluency to gain comprehension and therefore able to ‘read to learn’, below he or she is struggling to decode the letters and syllables and is ‘learning to read’. Recent analysis suggests the average speed for grade 2 (around 9 years) students in Tanzania is only 18 wpm, but less than 20% are above the required reading threshold.

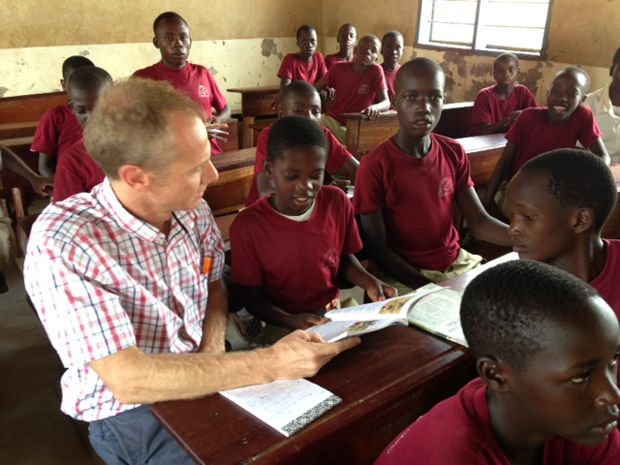

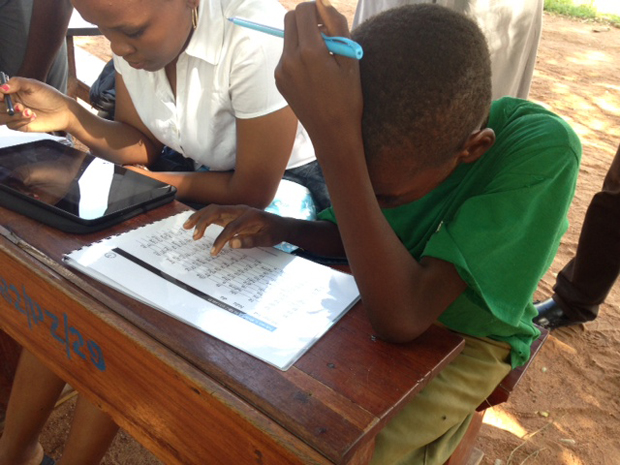

DFID’s new EQUIP-T programme of support to raising primary education quality in Shinyanga and a number of other disadvantaged regions in Tanzania has recently started. Still puzzling over the exam issues we continued to Pandagisha primary school where we able to observe EGRA reading and related maths and baseline survey work, in action. A team from Oxford Policy Management (OPM) were measuring the Swahili reading and maths skills of a random sample of grade 3 students. An impressive set of CAPI software tools were being used to structure the student tests, with the resulting data being download directly to avoid the need for any transcription that might introduce errors and delays.

Whilst I can't claim the 2 'unlucky' students we observed will gain directly from the experience - they looked very nervous with the surrounding Muzungu (foreigners), we do hope that the results will be worthwhile. In total 200 schools are being tested in this way, and this will be repeated in 2016 and 2018 to try and rigorously ascertain the impact of this large programme. Combined with more qualitative questioning and contextual evidence the OPM independent evaluators will try to help us better understand the intricacies of what is going on, or not going on and why.

Ben Ramalingam has made it plain to me that our somewhat linear theory of change for this programme: "teacher and leadership training, school supervision and management and community initiatives will translate into motivated teachers and more useful contact time with student in classrooms and ultimately more learning that translates into a better education and a skilled future workforce to build Tanzania’s economy and prosperity…" is hopelessly naïve and assumption laden. We hope the evaluation will dig into those factors of perverse intentions and community dynamics (will that new teacher from Dar es Salaam stick around and why?) to assist EQUIP-T to course correct and ultimately provide us with a reliable metric of more fluent readers at school, at a measurable cost that can guide the government into improving the nation’s education system.

Or perhaps digital native kids will fool us all and ‘fast track’ their reading ability with disruptive software tools such as Spritz to get up to a 1,000 words per minute? Really, try it for yourself….!

Keep in touch. Sign up for email updates from this blog, or follow Ian on Twitter.

Recent Comments