What do we mean when we say we are creating jobs in developing countries?

That's not as easy to answer as it might first appear. For a start, few people in developing countries are ‘unemployed’ as we might use the term in the UK.

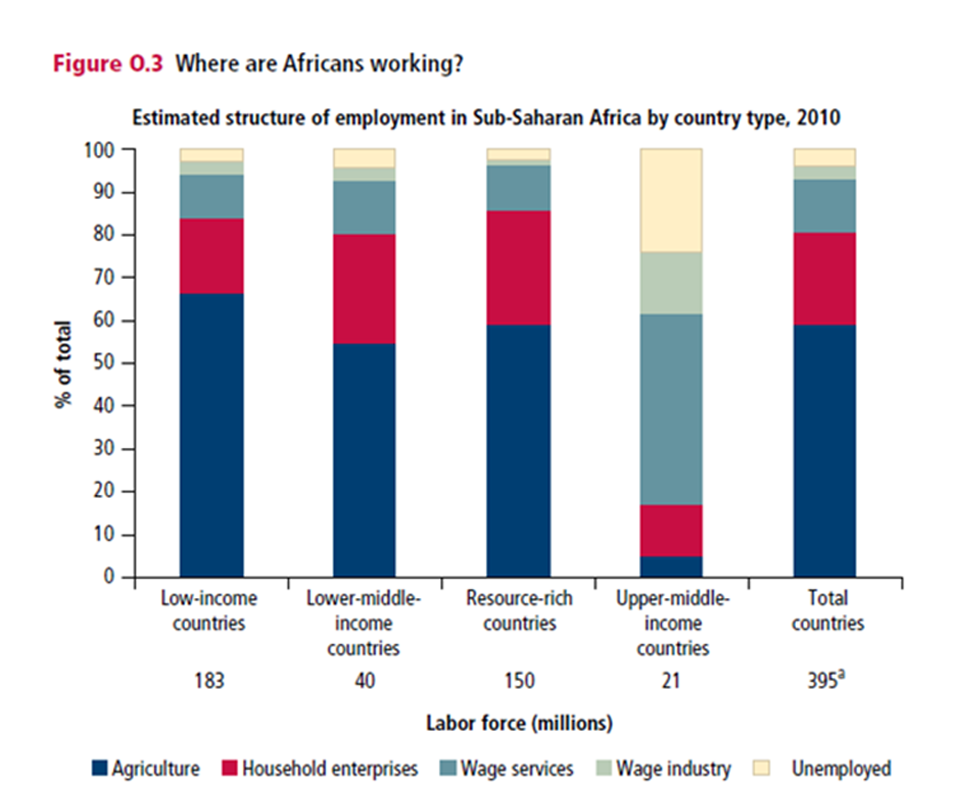

In fact, unemployment rates are relatively low in low-income countries. The graph below from a World Bank publication captures this really well.

What this illustrates is that few people in poorer countries actually have 'waged' jobs. Most are self-employed and work on small farms or in household businesses. This is work, of course, but the problem is, it's not generating the income needed to escape poverty and transform their lives.

I’m not saying self-employment and working in the informal sector is always a problem. But what is problematic is that it’s just not well paid and the conditions are likely to be worse or even unsafe.

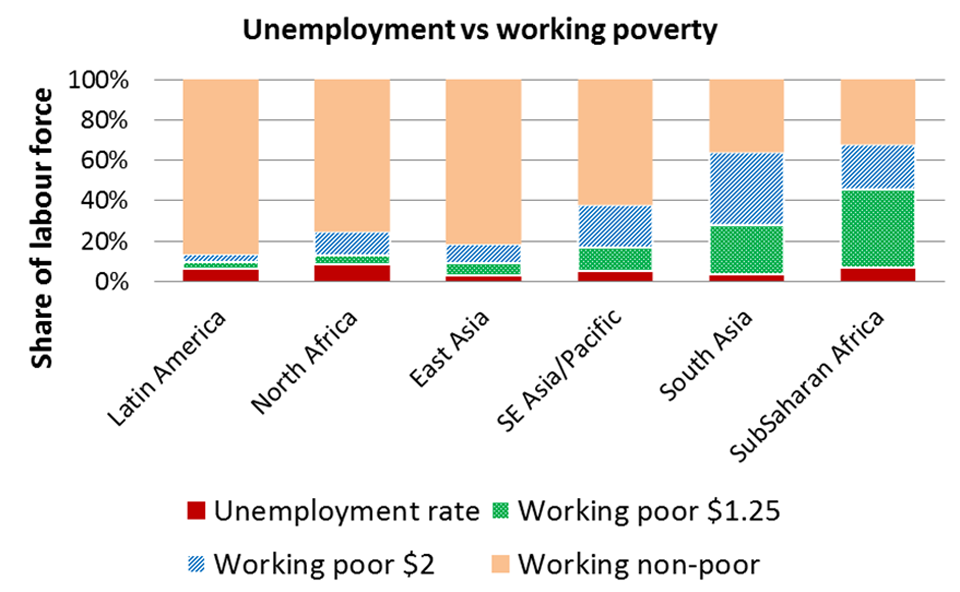

The next graph shows how many people in South Asia and Africa are working but in poverty. You might say the real problem is ‘under’-employment rather than employment. People are ‘economically active’ – they have to be – they’re just earning very little. More than half of people in Sub-Saharan Africa are working but are still in poverty (earning less than the $2 a day threshold).

I’d like to go one step further and set out what I see as the real jobs issues facing developing countries.

Here are my top 5:

- There are too few productive waged jobs in modern, formal sectors

- Most people are engaged in very low productivity or subsistence work in both rural and urban areas

- There are large gaps in job chances for women, youth and marginalised groups

- Much work is in poor conditions or is unsafe or risky

- Many labour market-related institutions are ineffective

So what do we do about jobs?

Creating jobs in their millions will need healthy growth processes.

By ‘healthy’ growth, I’m thinking economic growth that’s high, is sustained over long time periods and is inclusive – it creates jobs and the benefits are distributed well. This is easy to write but achieving it is a big ask. And that’s why DFID is focusing on economic development.

Our Secretary of State, Justine Greening, gave a speech at the London Stock Exchange in January on economic development. She said the word ‘job’ more than 10 times. Jobs are the reason why we care about economic development.

We also published an Economic Development Strategic Framework in January so you can see how we’re planning to scale up programming. (In fact, DFID is doubling how much it spends bilaterally on economic development between 2012/13 and 2015/16.)

DFID’s work on economic development involves:

- getting the international system right (think, ‘trade’ rules)

- getting private sector growth going (this means household enterprises and SMEs as well as larger firms)

- ensuring growth is broad-based and inclusive – in particular for girls and women.

We don’t do this alone of course: other development partners include donors, World Bank, ILO, think thanks and academia, business, NGOs and others.

Our work helps make progress on the real jobs issues in developing countries through (a) directly investing in firms and supporting marginalised groups directly and (b) improving the enabling business environment and institutions.

While DFID is doing a lot on jobs and planning to do more there is still plenty to learn. Is DFID and the rest of the international community doing the best things to tackle jobs problems? What do governments and donors have to get right to improve delivery on the jobs agenda? Here is a list of questions that are at the front of my mind at the moment:

What works - do we know enough when it comes to tackling jobs problems? A lot of important research at the moment is looking at the question of what interventions work and which ones lead to more jobs and higher incomes. The tough message is that some interventions might work in achieving their initial objective – for instance, training people or increasing access to financial services. But the link to jobs is often complex.

Counting additional jobs created due to donors – is this the first thing to get right? Or is it an impossible task? It is extremely important that we can communicate the impact we’re having on jobs. But there are pitfalls in claiming results around job creation that we, all international partner and indeed governments need to avoid. (For more on this topic, look here in Chapter 3 for an in-depth look at how the International Finance Corporation – the private sector arm of the World Bank – thinks about estimating job creation effects.)

Economic transformation and jobs – where are the jobs of the future for poor people going to be? Developing countries are urbanising and the proportion of people working in agriculture is reducing. How should DFID’s work on jobs be shaped in the light of these mega-trends?

Jobs data – the World Development Report 2013 on Jobs made the observation ‘Jobs are centre stage, but where are the numbers?’ Jobs statistics are really low quality and infrequent. How can this change so that governments and their development partners know how the big jobs picture is changing?

Thanks for reading and I’m looking forward to a lively discussion. I’ll write more on these issues and others in future blogs.

Keep in touch. Sign up for email updates from this blog or follow Stuart on Twitter.

4 comments

Comment by Lee posted on

The way that people get high income jobs is by selling their labour to people with high incomes, (who can afford to pay a decent wage). For people living in low income countries, this is inevitably always going to be a challenge, because most people in low income countries have low incomes.

So of course you're right to mention trade rules, but it's sad that there can be no discussion from DFID about possibly the quickest way to get a low income person a high income job - migration.

Comment by stuarttibbs posted on

Thanks Lee, I think this is a really important point. Economies are highly ‘connected’ in various ways that have a huge bearing on the jobs picture. Migration plays an important role in many countries – Nepal struck me recently as a country where migration and remittances are shaping the poverty and economic development story in the country.

Another major ‘connectedness’ issue concerning jobs is of course exports. Exports play a crucial role in supplementing domestic markets in low income countries. Labour intensive manufactured exports in Bangladesh and also in Ethiopia are rightly receiving a lot of attention now. Some of this is FDI related. The WDR had a nice chapter (no. 7) called connected job agendas - migration, trade, FDI etc.

Thanks for the comment (I will be quicker to respond in the future…) And I’ll bear in mind your view on DFID not giving much attention to the migration agenda. Thanks too Matthew for the thoughts on domestic imbalances.

Comment by Andrew posted on

You may find Gallup's global payroll to population figures of interest in response to your question "Where are the numbers?" http://www.gallup.com/poll/156944/global-employment-p2p-wednesday-story.aspx

Comment by Matthew Sellar posted on

Interesting and informative blog-post Stuart, thanks!

Just to respond to Lee - a lot of developing country workers are employed directly or indirectly by very profitable developed country companies (Chiquita - bananas, Zara - garments, Glencore - minerals, etc) catering to developed country consumers, but despite working for highly profitable entities these workers remain on low-incomes. This is a question of the distribution of added-value along the supply chain, and this contains a very political element: those who are powerful will appropriate most of this added-value and will not give it up without a struggle (Chiquita links to paramilitaries) or without experiencing some kind of pressure (Rana Plaza in Bangladesh).

Subsequently, redistributing value across supply chains is generally a conflictual and monumental task as it requires political, economic and social empowerment of those that are currently contributinig to producing added-value but relatively not "capturing it".

DFID's Trade Policy Unit has a programme looking into this called "Capturing the Gains", which may be of interest.