When the Girl Summit is held in the UK in July, one of the key messages will be the role of education in transforming the lives of girls. Education enables girls to participate more fully in their communities and their nations - politically, economically and socially. An educated girl is less likely to marry in childhood. And an educated mother is more likely to have healthy, better educated children. This is a global message.

When the Girl Summit is held in the UK in July, one of the key messages will be the role of education in transforming the lives of girls. Education enables girls to participate more fully in their communities and their nations - politically, economically and socially. An educated girl is less likely to marry in childhood. And an educated mother is more likely to have healthy, better educated children. This is a global message.

But how is education for girls seen in Afghanistan?

Recently, our project interviewed over 1,000 Afghan girls and their families. Almost all of the parents interviewed – 91% – believed that girls have the right to education. 70% of mothers said that they wanted their daughters still to be in school when they were 18.

But the reality is different. Far less than 91% of girls are enrolled in school. By the age of 15, girls’ attendance has fallen to just 35%. The gap between what parents are saying and what they are doing is troubling.

So what’s keeping girls out of school?

There is a strong connection between the distance a child has to walk to school and the likelihood that they will attend. Here in Afghanistan, that’s especially true for girls. That’s why we have established community-based classes, so that classes are never more than a few hundred meters away from a girl’s home.

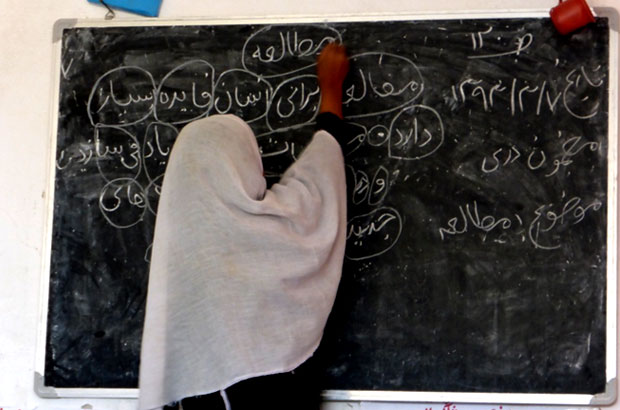

Secondly, many communities discourage contact between unrelated men and women - so we train female teachers, using female field staff. We also train women to become school management committee members, who then visit girls’ classes once a week to ensure that everything is running smoothly.

We also found some surprises in the survey. In most of the world, poverty is a barrier to education: families cannot afford school fees, or household income may depend on the children’s labour. But we found that families who were struggling economically were actually more likely to send their daughters to school. That’s important, because it means that parents see education as an investment for the future.

There’s more to the decision to send girls to school than distance and economics however. Our interviews showed that mothers with daughters in school have fundamentally different perceptions than mothers in households where girls don’t attend school. A mother with a daughter in school is more likely to think that the nearest primary school is close, safe and easy to reach than mothers whose daughters don’t attend – quite independently of how close the school actually is. Mothers whose daughters attend school are also more likely to believe that girls can learn as much as boys and that the wider community supports education for girls – even when the 2 mothers belong to the same community.

These kinds of perceptions are much more difficult to address. But we are seeing positive changes. The story of 11-year old Fahmida is an inspiring example:

“When I saw that the boys and girls in our village were going to school, I was interested and wanted to go to school too. One day the mullah told my father about some people who had come to our village to start classes. The mullah encouraged my father to send me and my elder sister to study. I felt very happy. However, after some time my elder brother stopped me from going to class because his friends told him that it is not good for girls my age to go to school. That made me very sad.

Our teacher asked the mullah to talk to my father and ask him why I was not attending classes. So the mullah and other elders came to our house and advised my father to let me return to classes. My father told my brother not to stop us from attending school and to tell his friends that the mullah had decided that we should go back to school.”

This account provides a model for tackling the barriers that keep girls out of school: make education easily accessible; be sure that it is culturally appropriate and show families the benefits of education. Communities must also take ownership - it was not project staff who intervened to get the girls back to school, but a teacher, the mullah and community elders.

We may not change everyone’s mind about education for girls in Afghanistan, but our project is already changing the minds of tens of thousands of parents. That’s a pretty good start.

The Girls’ Education Challenge is the largest ever global fund dedicated to girls’ education and calls on NGOs, charities and the private sector to find better ways of getting girls in school and ensuring they receive a quality of education to transform their future. DFID investment will help up to 1 million of the world’s poorest girls in 22 focus countries.

———————————————————————————————

Please note, this is a guest blog. Views expressed here do not necessarily represent the views of DFID or have the support of the British government.

Keep in touch. Sign up for email updates from this blog.

Recent Comments