Last month I joined Justin Lin – the ex-Chief Economist of the World Bank and something of a rock star in the world of development economics – to talk at a conference in Geneva organised by the Donor Committee for Enterprise Development.

Justin tells a powerful and exciting story about how Africa can attract 85 million jobs from China and Asia. That’s more waged jobs than there are in Africa at the moment (about 60 million based on the Filmer/Fox graph in my last blog). But, as he says, this investment will not happen without changes in the investment environment in Africa.

There are key things that need to be put in place: reliable transport networks, a constant supply of electricity, efficient bureaucracy to handle taxes and get goods in and out of the country and a skilled labour force.

When it was my turn to speak, I argued that ‘jobs’ is not a distinct area of policy and programming per se. Most of the work DFID does to support economic development can in turn support jobs - but we need to better understand how different growth paths and different policy options impact on jobs.

I suggested that policies for job creation cover a spectrum ranging from ‘enabling’ interventions to ‘targeted’. The balance depends on our diagnosis of the growth and job constraints in a country.

We need to make sure we balance our policies that can get growth going, attract investment and connect with the global economy. But we also need to be mindful to tackle any obstacles that may prevent a business from succeeding or which hinder some of the poorest people, including women and young people, getting a job. This may mean tackling bottlenecks to businesses succeeding or obstacles to the job chances of the poorest or excluded groups, including women and youth.

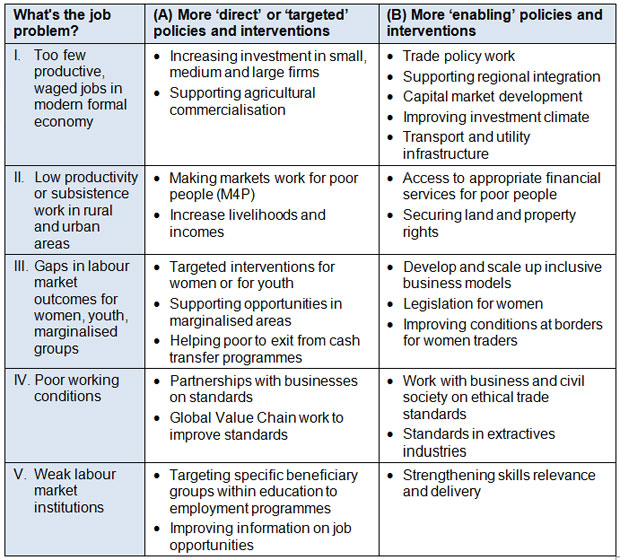

In my last blog I introduced a set of 5 ‘jobs problems’. I’ve used them again in the table below to show the different ways that DFID programmes impact on jobs. The policy and programme areas are split into 2 groups:

(a) Those that are more ‘direct’ or ‘target’ particular constraints; and

(b) More ‘enabling’ interventions that support the economy at large.

Let me give you a few working examples to put these into context:

- To increase the number of waged jobs in an economy the Commonwealth Development Corporation – CDC – invests in firms helping them scale up their plans to employ people. Firms that CDC invests in need to comply with work conditions for their employees to make sure they are safe. Many interventions will tackle multiple jobs problems.

- To tackle pervasive low productivity employment, DFID supports programmes that helps to increase the incomes of people in targeted poor groups – such as the ‘making markets work for the poor’ approach. Extending access to financial services to people helps address another important bottleneck to better economic opportunities such as we’ve do in Kenya and Pakistan. In Somalia training is helping women access better income earning opportunities.

- DFID’s work to improve land and property rights for 3.8 million men and women across Rwanda, India, Nepal and Mozambique will help provide opportunities to increase incomes in combination with other factors.

- To improve connectivity to markets we support increased investment in transport infrastructure and reducing barriers to trade in East Africa. We’re also supporting work with governments and customs authorities to improve conditions for female informal traders who face harassment and extortion at borders.

To sum up, DFID’s work helps make progress against the real jobs problems in developing countries through directly targeting specific constraints and improving the enabling environment. We need to get healthy growth processes going and we need to be smart about ensuring people are included in these growth processes.

But getting the right mix of enabling and targeted interventions for any context requires understanding what’s limiting job creation and causing the jobs problems we see.

Next time I’ll look at some of the perspectives and tool kits that are out there for looking at the nature of growth in an economy – or the lack of it – and diagnosing jobs constraints.

Keep in touch. Sign up for email updates from this blog or follow Stuart on Twitter.

Recent Comments