Having arrived in DRC just over a month ago, I was incredibly lucky to be taken with Alastair and Mischa - colleagues from the DFID DRC humanitarian team - to see our programmes in the east. Having seen that special security permission was required from London as one of the roads we were travelling on bordered a ‘red’ road (needing military escort), I have to admit I was a tad nervous. Visions of flak jackets and emergency operations were still at the forefront of my mind as we took off from Kinshasa early on Monday morning in the UN plane.

A year ago there were an estimated 600,000 displaced people in South Kivu and armed groups were fighting with the Congolese army and each other across the province. In the past 12 months, there have been improvements with the defeat of the M23 rebel movement. Numerous actors, including the Congolese government and the UN mission in the DRC have declared that peace and stability are returning to the eastern Congo. But the reality is armed groups and the army are still fighting each other and committing human rights abuses across the province. The number of displaced people has barely changed.

I wanted to see for myself how DFID is able to deliver in such a difficult context. Our first stop was in Luntukulu, South Kivu, where girls and women, supported by the International Rescue Committee programme ‘Saving Lives, Saving Futures’, told us how very basic ‘Dignity Kits’ (including torches, sanitary pads, clothes, and whistles) had made a huge difference to them being able to move around the community more safely at night. As a result of training provided by IRC staff, women now knew how to get help if they became victims of rape or other violence.

But the limits of the humanitarian response soon became clear when we visited a government-run health post in Culwe, South Kivu. Tucked amidst green rolling hills, Culwe is a stunning location but far from peaceful. A kilometre behind Culwe sits a Congolese army base, and a few kilometres beyond that local armed groups make the risk of conflict and violence a real one for the local doctor and his team. This is in addition to the challenges presented by a weak health system and lack of resources. The young doctor told us he could no longer buy drugs after the ‘humanitarian money’ ran out and asked us to ‘pass the message on’ to Kinshasa. As we drove off I wondered if he had made this request to others before.

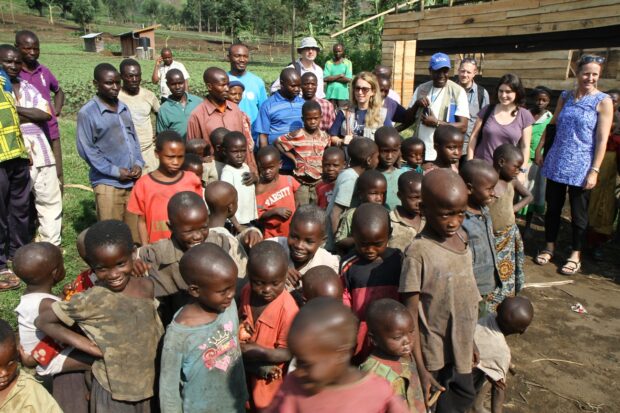

The following day, accompanied by a team from UNICEF, Catholic Relief Services and Caritas, I was taken to a fascinating and innovative programme - Alternative Responses to Communities in Crisis (ARCC) - which is providing cash transfers to schools via mobile phones. This money is used to put in place school improvement plans such as building classrooms and paying school fees to allow more vulnerable children to attend these schools. Although early days, school enrolment figures were rising as a result. And parents and communities now also know how the money is spent. In my eyes, this was an excellent example of how we can be innovative and push longer term governance reforms, whilst also responding to immediate needs.

So, what after this short trip, were my ‘take aways’ ?

Firstly, the needs in the DRC are enormous and outstrip the resources. Perhaps this is why DFID’s programme in the DRC is covering a fairly broad spectrum of programmes from humanitarian and conflict prevention, governance, delivery of basic services (health, water & sanitation, and education), to a new private sector development programme working to improve the business operating climate. In a country were the needs are so huge, this seems to me to be the right approach. But it also means more than ever we need to work with others to coordinate effectively and make the links between these programmes.

We also need to be nimble. The often-cited ‘relief to development continuum’ seems difficult to apply in eastern DRC, with frequent and shifting pockets of instability but also areas where there seems to be relative calm. As Mischa explained, “we need a response that is appropriate for the type of conflict we see here: a response that is permanently on standby and assessing the changing situation; a response that can respond to movements of populations quickly and appropriately, even in remote and difficult environments; and a response that isn’t dependent on waiting for donors to mobilise new funding for each outbreak of fighting.”

My other lasting impression after this short week in the Kivus, is that whilst people have and continue to suffer from conflict and displacement for a period of over 20 years - there is also a certain ‘stability in the instability’. People have fantastic resilience which has allowed us to operate in this difficult environment and to seize opportunities that can have a real impact. So, to my ‘newby’ eyes, I am hopeful.

Keep in touch. Sign up for email updates from this blog, or follow UK in DRC on Twitter and Facebook.

2 comments

Comment by Ali Khim posted on

I wonder why DR CONGO has never has never been stable ever since it got independence yet its one of the African countries with a wide pool of minerals all half of the country. I think program directors of various non profit orgs should first focus on grounds of creating a peaceful country out of CONGO, by eradicating wars and then focus on other issues of providing food, health and other essentials

Comment by Jane posted on

Yes, we need to be nimble and open minded! Great article