In the spirit of the UK aid watchbody ICAI's recommendation to ramp up institutional learning within DFID, a welcome initiative for advisers like myself is to support programme design and review in other countries, promoting the sharing of experience and knowledge. I was dispatched from Tanzania to Malawi to help review a major education programme supported by the UK that has been in operation for the last few years.

Inevitably one draws parallels between regional neighbours. After the torrential humid storms and traffic chaos in Dar es Salaam, the cool, sleepy, green rolling hills of Malawi was very engaging. Major elections were due in a few weeks and campaign posters lined all major roads, but this did not disrupt a schedule of meetings and school visits.

The story from the capital city Lilongwe was fascinating; a major programme of school construction, books and teacher training all co-financed with pooled donor support. Very familiar sounding bottlenecks in the early days - bureaucratic delays and erratic fund flows, which then were unexpectedly destructively amplified and compounded by economic shocks in 2012 and 2013. The linear results chain broken: pooled funds delivering inputs to smaller better resourced school classes and happy kids 'learning for all'; as assumptions didn't hold. Political instability when President Bingu wa Mutharika died unexpectedly in office and exchange rate controls being relaxed leading to rapid currency devaluation. A year later major corruption allegations emerged that led to a suspension of UK and other donors' financial aid. Senior Malawian education managers I met seemed dedicated and competent, but how do you settle multiple contractual disputes and demotivated teachers as the buying power of the Kwacha dropped and building contractors down tools?

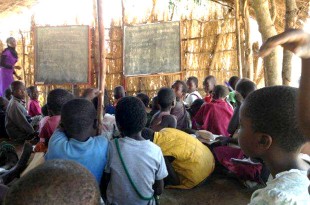

In rural schools not far from the Mozambique border the situation was very mixed. Good looking new classroom blocks and teacher housing being finished, school grants arriving enabling head teachers to purchase essential supplies and materials. But why next to the new teacher’s house were 40 children learning under a tree and inside bare classrooms older kids had to strain forward to write on a bare dusty floor? Huge 100+ class sizes in the entry grades was common, but with high rates of attrition only a fraction were enrolled in the upper primary classes and even there prospects to enter secondary school were very limited.

The macro shocks that affected both Malawi and the education programme had however had some positive effects. Necessity is said to be the mother of invention and Malawi Malaise had it seemed been breached with a range of promising initiatives being scaled up. An effective unit using a decentralised community model was now managing most school construction; teachers were being recruited locally and trained using open and distance learning methods to address the shortages. Funds were arriving in schools and a complimentary non-formal learning model was being scaled up for out of school children in remote areas.

Land-locked Malawi is currently not growing rapidly like many of its coastal neighbours on the back of extractive industries - minerals, gas and oil. Should it try to follow Tanzania with a major rapid growth in secondary schooling, and if it did what are the jobs and opportunities for its youth?

While sector planning and modelling analytics are undoubtedly needed to plot a sensible course and prioritise for expansion in the coming years, an impression was reinforced that another major drive on building and teacher recruitment would require a lot of nuancing. How could children learn more in very constrained conditions and how could future programmes be more agile?

Or will the killer assumptions in the logframe always drive relative success and failure and perhaps we should be more accepting of this and expect uncertainty and the need for change and reform?

Keep in touch. Sign up for email updates from this blog, or follow Ian on Twitter.

2 comments

Comment by Owen Muluzi posted on

Political upheaval can have a massive influence in programming. It really has to be shown if costs escalation has led to these problems.

The challenges remain tall; the evergrowing debate of secondary versus primary education is quite a challenge as well. There is an added dimention of tertiary education.

Quite interesting discussion here.

Comment by Ian Attfield posted on

Indeed, post eelection I hope Malawi can make progress on these complex choices,

best Ian