Those of a certain vintage might recognise the title of a Johnny Nash single from 1972. The lyric goes on "And the more I find out the less I know". I sympathise with the sentiment.

I arrived in the Pakistan office of the UK's Department for International Development (DFID) where I lead the team that supports better governance. This includes practical measures to improve law enforcement and justice sectors, the delivery of government services like health and education, and public awareness so that people can demand accountability of their elected officials. Another part of our team deal with humanitarian emergencies – helping people who have lost their homes, their loved ones and their means of livelihoods through conflict and natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes.

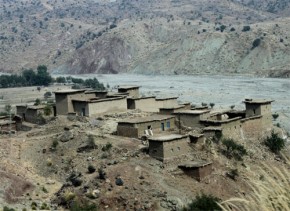

Last month I visited South Waziristan, a district in the troubled Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), a semi-autonomous region of Pakistan that borders Afghanistan. FATA has a total land area of 10,510 square miles with a population of about 3.2 million. The visit was a rare event - no one from DFID has visited in recent years. But this sort of field trip is vital to help people like me start answering some of the questions.

Both North and South Waziristan are somewhat notorious because serious conflict between radical Islamist fighters and Pakistan government's armed forces raged here between 2009 and 2010, which caused over 2 million people to flee, seeking shelter, protection and survival in safer parts of the country. This is a massive wave of displacement – imagine twice the population of Glasgow on the move – and represented almost two-thirds of the entire population of FATA. People left with little notice, packing whatever they could but leaving so much behind, including livestock and their worldly belongings - their whole life's savings, to find safety. And they had good reason: thousands of homes were damaged – the UN says that 20% completely destroyed - as well as destruction to schools, clinics, roads and basic infrastructure.

Even before these troubles people here were known to be among the poorest in Pakistan; only 7.5% of women are able to read and write, very few communities had clinics or schools, safe drinking water or toilets. But they had relative peace and a form of income from agriculture, raising cattle, goats and sheep and living a centuries-old traditional existence that was held together in a delicate balance of power between tribal chiefs and extended family networks. Alexander the Great found his army held up by ancestors of the FATA and more recent British expeditions through the region found these mountain tribes to be fearsome and impossible to overcome, agreeing finally to pay for their services as guards of the frontier province.

But there is no historical precedence for the extent of killing and displacement that has taken place across FATA since 2008 – roughly 1.5 million people are estimated to be living with relatives in Peshawar or other towns and cities. About 100,000 of these people live in camps set up by the UN, where they receive basic services including food, education and health care. These are hard conditions, especially for the close tribal communities accustomed to their relative isolation in mountain valleys and there have been many cases of abuse and exploitation of unemployed youth, girls and women.

It isn't just the displaced people that are affected in these situations: communities that host thousands of "long-term guests" also feel the effects before too long. Basic services like water and education suffer when you double the demand. So last year our humanitarian team in DFID worked with UNICEF and NGOs to help these "host communities" to cope with the dire water and sanitation crisis in towns, villages and camps. We also supported fledgling return efforts in rural areas, again in water and sanitation projects but also helping to re-stock goats and chickens and resume agriculture and small businesses so that people could re-start their own livelihoods and be less dependent on aid. This is a big effort, aiming to reach up to 1.3 million people from within the war affected displaced community as well as those hosting them.

Now, after several years of concerted government efforts people are slowly returning to South Waziristan. Going home when so much has been destroyed is not an easy prospect and I went to see how people were getting on. I have to say it was impressive how much the government and the military has done so far to encourage return, as well as projects of the UN agencies and different donors. There are new roads, clean water pumps, a technical college that could help re-start businesses, a school for girls, another for boys, a clinic, even a sports stadium and market stalls. I met people who had been among the first few to voluntarily return (mostly men because women are not encouraged to meet outsiders) who were really warm and friendly. I learned from them that people would regularly walk from up to 12 km away to visit the refurbished market we were standing in; and that some of the really important things that make people want to return home are really very simple – such as housing and availability of water.

One of the questions we are considering is how best to help make the conditions right for more returns to FATA, so that the government and people of Pakistan can lead the work to help the poorest and most vulnerable; drawing in international support to help where necessary. Governments, charities and other agencies such as mine need to consider what sort of role is best for us to play for immediate and longer-term work on health for example, or the provision of educational opportunities for all children? How we should coordinate with government efforts and other donors so we complement each other’s work, and invest only in things that deliver real and tangible results that we can be proud of.

But first we need to know if people are really going to return, and if so how many and when? And what are the obstacles to return now? What happens if people stay where they have found refuge these past years? What will happen once international combat forces pull out of Afghanistan next year?

As I said, more questions than answers for now, but visiting these early signs of recovery have been inspiring. They are signs of hope.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Are you interested in development issues and the UK's support to Pakistan? Sign up to receive our quarterly newsletter which includes new announcements, case studies, photos and blogs on our work as well as jobs and funding opportunities.

2 comments

Comment by zafar Gondal posted on

Dear Bill,

I appreciate the work you are doing in those neglected areas. My understanding of the issues is weak or lack of institutions in some cases or in other cases institutions are dominated by certain powerful groups and are not accessible to the vulnerable, laws are not shared and consultative and laws are made without taking into consideration needs of the users. Laws need to be users friendly and focussed. Law should not make criminals. People have no voice in making of laws, in governing the area. Of course, education, skills are very important as well.

In my view, the support in four areas is very vital for sustainable solutions of the problem pakistan is facing now: 1) independent, consultative legislative process, 2) independent, impartial and accountable judiciary, 3) independent election commission, and 4) an accountability system at all level of government.

Comment by Humayun Gul posted on

Fantastic! to know about your visit to SWA, Bill.

Your article just refreshed my memories as I recall my field teams in South Waziristan had just closed both the community infrastructure and food security projects (funded by UNDP and UNOCHA) in the Sararogha and Sarwekai areas of SWA. I remember they mentioned a donor-mission was soon to visit SWA and I had sent out staff members to support UNDP officials who wished to be guided on ground in Waziristan while my second team was on its way to Tirrah Valley in the Khyber agency for implementation of emergency shelter project funded by UNOCHA and also to assess water sanitation needs in Tirah (later funded by Rapid Fund of OFDA/USAID) where almost 22000 IDPs had returned by October 15th 2013.

It is really wonderful to find what you guys are trying to do. I also agree to the questions you have put down in the article and as you may agree the answers are not very simple. The UNDP conducted a ERAF assessment across FATA which gives out a general idea about the needs but the accuracy of the data may be contested and also the fact that the changes on ground are too drastic and high impact. A year old data may be totally useless. Similarly, too idealistic solutions are also not going to work, at least not in the immediate future. Yes, a policy of participation and public engagement would pay off, but of course, after returns to areas of origin.

Based on 15+ years of working experience in FATA and KPK humanitarian and development sectors I would suggest very well though and planned interventions surgical by nature, based on ground needs and realities and conscious to local contexts and culture, and designed under a broader programme e.g a FATA Peace, Stability and Development Programme with clear objectives and immediate, short, medium and long term objectives but flexible, dynamic and adaptable to changes as and when needed. This may only be a broader framework and detailed programme can be designed on the basis of more concrete data.